19 Dec RIABiz: How Morningstar got in the last word after The Wall Street Journal dropped a year-in-the-making investigative piece on the fund tracker’s head

Don Phillips used Chicago street talk and wielded research muscle to hit the Dow Jones newspaper high and low

December 19, 2017 — 12:12 PM PST by Oisin Breen

Brooke’s Note: The Wall Street Journal was once a great business-to-business publication. But in a digital age, as consumer-side readers’ clicks got easier to come by, WSJ’s coverage tilted. Now, its political reportage, for example, is excellent. But once in a while, the Journal takes a stab at showing it still has B-to-B street cred. It’s broadside over the Morningstar bow in “A Morningstar mirage” is one such example. Sure, the Journal makes some good points. But its attempted takedown of the giant researcher and its star-rating system suffers from a lack of fluency in talking business. The problems begin with its journalists’ seeming ignorance about the news. The star-ratings system’s shortcomings as presented in the paper are, I’d argue, well-argued but well-trampled ground. Second of all, the Journal does not seem to understand that the advisor world now tilts heavily to fee-based guidance. Its examples of star-rating abuse seem to go to brokers looking for a way to sell funds in a transactional environment. The third factor springs partially from each of the first two. In its thirsting for corporate profits, Dow Jones itself purchased a controversial ratings system from R.J. Shook several years ago, one that assigns rankings to human financial advisors. See: Getting inside Barron’s Top-100-Advisor lists with some help from Sterling Shea. Like the star ratings, its “top” ratings look exclusively into the rear-view mirror and derive giant revenues by turning around and selling those ratings back to the advisors themselves as marketing fodder. Morningstar did not raise that issue in rebutting the Journal but to me it seems too big an irony to ignore.

The Wall Street Journal got its jabs in during a rare bare-knuckle exchange with Morningstar Inc., but it’s the venerable Dow Jones publication that may end up seeing stars. See: Morningstar bristles about being ‘refused or ignored’ by DoubleLine as the ‘silly, ugly feud’ between Jeffrey Gundlach and the ratings firm rages on.

In this corner is the New York-based Journal, part of the Murdoch media empire that spans 120 newspapers in five countries and has the largest newspaper circulation in the United States.

Defending its title is Chicago-based Morningstar, an investment research and investment management firm that rates the $16-trillion mutual fund market sector and has more than 250,000 advisor subscriptions on its research platform. See: Morningstar renders ETF verdict by discontinuing ETF-only conferences after category becomes the Vanguard-BlackRock show.

Three bylines, one year

On Oct. 26 the Journal printed a front page investigative three-byline article with the provocative headline, “A Morningstar mirage: Investors everywhere think a five-star rating from Morningstar means a mutual fund will be a top performer—it doesn’t.” (The article first appeared on the WSJ.com website Oct. 25.)

“Millions of people trust Morningstar to help them decide where to put their money,” the Journal stated. “Funds that earned high star ratings attracted the vast majority of investor dollars. Most of them failed to perform.”

That said, the more than 4,000-word article by Kirsten Grind, Tom McGinty and Sarah Krouse pursued the angle that Morningstar’s Analyst Rating for Funds, rolled out six years ago as forward-looking ratings, are also counterproductive. See: Morningstar explains its new forward-looking rating system — and tosses in some hot fund picks for good measure.

The publication also strongly implied that Morningstar’s relationship with giants like J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and BlackRock Inc. may not be wholly kosher. “[BlackRock] has a team that works to persuade Morningstar analysts of the merits of various funds, [and] BlackRock CEO Laurence Fink met with Morningstar analysts early this year to discuss the firm’s ratings. In May, Morningstar upgraded to positive BlackRock’s ‘parent pillar’

[analyst] rating.” See: BlackRock solicits more regulator scrutiny of robo-advisors, eliciting jeers and a cheer.

As the war of words rages on, research firms like New York-based CFRA hope to capitalize on the fallout and win business from Morningstar.

“Since the WSJ article we are hearing from many advisors that want either a second opinion or one that goes beyond a fund’s track record.” Said CFRA’s senior director of ETF and mutual fund research Todd Rosenbluth. “While more research has always been important we think the WSJ opened many eyes that were misunderstanding what they had. CFRA expects to continue to win business as we provide a more complete and forward-looking fund rating.” See: Bill Gross jumps back in the ‘total return’ game, first with a one-client, $100-million SMA, he tells P&I, but with a mutual fund on the way.

On the day the story appeared on WSJ’s website, Morningstar responded with a message from the CEO, Kunal Kapoor, on its own website, headlined: “Morningstar is relentlessly committed to independence, integrity and transparency.” See: How Joe Mansueto’s CEO hand-off to Kunal Kapoor could be more than a succession play for Morningstar.

On the day the story appeared on WSJ’s website, Morningstar responded with a message from the CEO, Kunal Kapoor, on its own website, headlined: “Morningstar is relentlessly committed to independence, integrity and transparency.” See: How Joe Mansueto’s CEO hand-off to Kunal Kapoor could be more than a succession play for Morningstar.

“The Journal’s own analysis found that 5-star funds outperform 4-star funds, which outperform 3-star funds, which outperform 2-star funds, which beat 1-star funds,” Kapoor wrote. “That’s not a mirage. That’s tilting the odds in investors’ favor …. We don’t apologize for serving as an influential, independent voice for the investor. This doesn’t always sit well with fund companies whose products we are independently evaluating, but our mission is to help investors. Not fund companies.” (Kapoor also shot off a letter to the editor, which appeared in the Wall Street Journal Nov. 2.)

Yet Kapoor may have relied too heavily on corporate-speak to justify a star-rating system that, the Journal had implied, delivers far less than its promise.

Jeffrey Ptak, head of global manager research for Morningstar, also took a crack at the Journal article the day it came out in a piece of brilliant researcher repartee that attacked the paper’s methodology and conclusions.

Under the headline “Setting the record straight on our fund ratings,” he wrote: “Essentially, the Journal was looking to see whether medalist funds (Gold, Silver, Bronze) had higher star ratings over the ensuring three- and five-year periods than non-medalists (Neutral and Negative). We had counseled the Journal against using the star rating as a measure of the Analyst Rating’s predictiveness for a simple reason: The star rating is based on funds’ trailing risk- and -load-adjusted returns versus category peers. But when analysts are assigning Analyst Ratings, they are not taking loads into consideration. So there’s a mismatch of the two, a point we made to the Journal in urging them to reconsider the star rating in favor of a risk-adjusted measure like CAPM alpha. They opted against our advice.”

Sinners wanted

Perhaps Morningstar realized it had missed the mark yet again — some of the 74 commenters on the site seemed to think so — because the next day it brought out its heaviest hitter in Don Phillips, the firm’s legendary research director and current managing director, who wrote a post titled The Wall Street Journal’s statistical fog.

If Kapoor and Ptak felt a need to play by the polite rules of intellectual discourse, Phillips was having none of it, free swinging at his adversary and the arguments themselves with equal ardor.

“… throughout my career at Morningstar, I’ve realized that most investors lack a basic numerical grounding and are therefore vulnerable to misleading statistical analysis,” he wrote. “I’ve even seen industry professionals fall prey to flawed use of stats. Unfortunately, these flaws are on clear display in The Wall Street Journal’s recent high-profile piece on Morningstar and our star ratings. The great irony is that The Wall Street Journal’s own numbers show the efficacy of the Morningstar Ratings, but its writers fail to grasp this insight.”

Then he delivered the blow designed to land where it would hurt the Journal most: it’s reputation.

“Investors have many parties trying to take a slice of their money, but few forces trying to tilt the odds in their favor. By the Journal’s own analysis, Morningstar’s ratings push the needle in the correct direction [toward investors] — while costing absolutely nothing and being widely available. If that is a sin, then perhaps Wall Street needs more sinners.” See: Page One Wall Street Journal article is a ‘home run’ for the RIA industry.

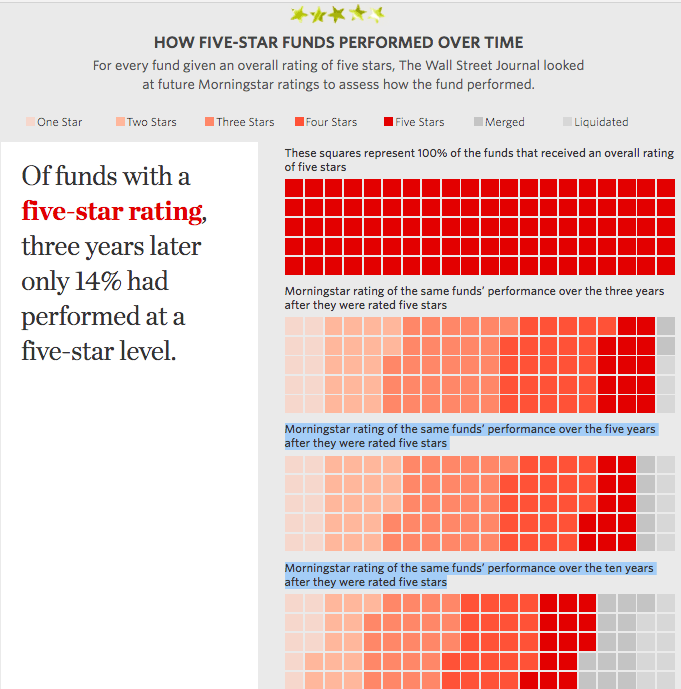

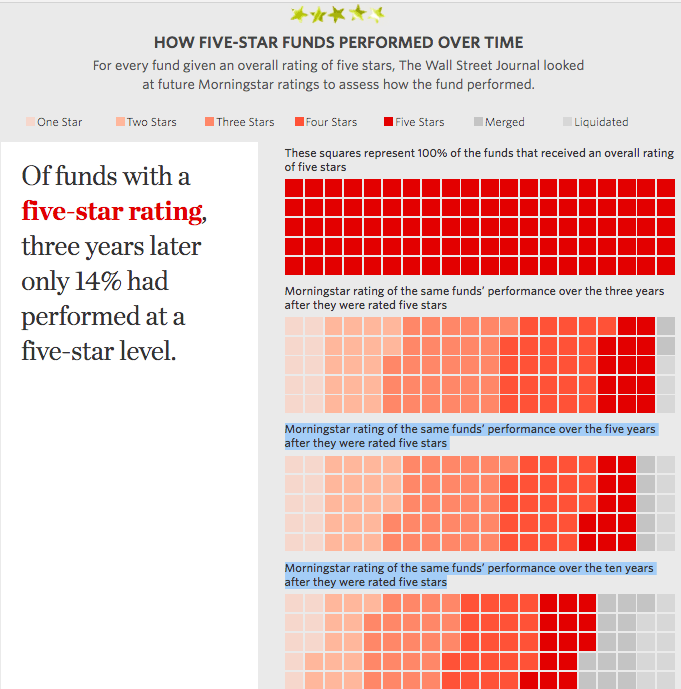

Phillips continued: “The Journal’s dismissal of small advantages is precisely the human dynamic that casinos and many financial-services companies use to exploit their customers. If choosing from the pool of 5-star funds gives a 14% chance of generating five-star performance, then it has increased an investor’s chances of holding a future 5-star fund [one of the top 10% of performers] by 40%. That’s a sizable win, but oddly the Journal writers present that performance as a disservice to investors.”

Year in the making

The Journal’s broadside was a year in the making and the product of interviews with dozens of current and former Morningstar employees, fund officials, financial advisors and investors, according to the paper. Kapoor spoke on the record for the story as did Ptak and Joe Mansueto, founder and executive chairman. Reporters interviewed more than three-dozen executives at asset management firms, although few would go on the record, according to the Journal. The publication shared the methodology for its conclusions in the story.

Morningstar’s Analyst ratings assess a fund’s ability to outperform the market, and are assigned on a graded basis from Gold through to Bronze, Neutral, and Negative.

“A lot of investors, and the people paid to guide them, take for granted that the number of stars awarded to a mutual fund is a good guide to its future performance,” the Journal argues. “By and large, it isn’t. Morningstar’s reach is so pervasive that the ecosystem for buying and selling mutual funds revolves around it.” See: How and why Morningstar sliced 16 bps for RIAs by dumping third-party mutual funds and stamping its Switzerland brand on its own mutual funds.

In response to the Journal, Kapoor denies Morningstar is culpable for misuse of the company’s ratings.

Star ratings don’t kill clients, star-wielding advisors do

“We have always said the star rating is a starting point for research and therefore shouldn’t be the sole basis for assessing a fund. Despite that, some advisors use it that way, a practice that shortchanges clients, who are denied the benefit of a more thorough research and fund selection process.”

Morningstar also firmly rejects that its Analyst Ratings alone provide sufficient grounds for investment decisions.

“The Analyst Rating is not a market call, and it is not meant to replace investors’ due-diligence process,” the firm explains on its website. “It is intended to supplement investors’ and advisors’ own work on funds, and, along with written analysis, provide a forward-looking perspective into a fund’s abilities.” See: With kid gloves and after great patience, Morningstar yanks gold-level rating on PIMCO Total Return Fund and predicts possible exit of ‘tens of billions’ in assets.

One of Forbes’ Top Millennial Advisors, Sterling Neblett, founding partner of Centurion Wealth Management, whose RIA, Spire Wealth Management LLC, has close to $1.9 billion of AUM, speaks highly of Morningstar’s research, but explains his firm pays little attention to ratings.

“We have always ignored the star rankings,” says Neblett. “We have taken a look into their newer medal ranking system which we do prefer and pay attention to but still do not weigh it very heavily into our decision making process. In conjunction with Morningstar, we also use Zephyrs and CFRA. However, we are using these systems more for the data, rather than their rating systems.”

It does indeed seem ironic that The Wall Street Journal would find fault with Morningstar’s ratings for documenting the effects of capitalism in a competitive market like the U.S. money management industry.

But more surprising to some knowledgeable insiders is that the article presented as news that Morningstar’s star-rating system relies on past performance — a criticism that has been leveled at it for decades.

Morningstar’s star-rating system categorizes and compares more than 10,800 mutual funds and close to 39,000 share classes into 100 groups relative to investment style or area. The top 10% in each group is rated as a 5-star fund, and the bottom 10% are rated as 1-star funds.

The Journal’s main thesis — that top star-rated funds suffer a steady decline in performance over time — can be traced back to 1999 in an article written by Matthew Morey and Christopher Blake and, more recently, in a 2009 article by Robert Huebscher, CEO of Advisor Perspectives Inc.

“It would be embarrassing to those involved if they could report only that they reconfirmed existing findings and did not uncover anything new,” Huebscher says. “The longer an investigation like this goes on, the more pressure there is to publish something that the researchers believe is new and meaningful.”

He continues: “If the WSJ had asserted that advisors already understand that star ratings are not predictive of future performance and that they do not rely on them for this purpose, then they would have had a weaker and less compelling story.” See: Morningstar’s Mansueto views next horizon: rating RIAs.

CFRA’s Rosenbluth disagrees. “Many advisors rely just on the star and will give clients a prior best ideas list. I don’t believe this is smoke not fire. CFRA has spoken to many advisors that only choose 5-star funds and Morningstar’s own research shows that money goes into 4- and 5-star funds and flows out of lower-rated funds.”

“There are many ‘bad’ advisors in our industry who rely solely on the star system and do not perform their own due diligence or do not incorporate other metrics,” Neblett accepts. “[However] this [WSJ] article has not changed our research methods. We still feel Morningstar is a great research provider. They gather vast amounts of data which we can easily use in our own research and due diligence process.”

RIABiz contacted Morningstar, The Wall Street Journal and the journalists behind the story for comment. Neither the WSJ nor its journalists responded in any way. Morningstar declined comment but sent links to the published responses of Kapoor, Ptak and Phillips, which included a comments section that includes plenty of views that dissent from its own constituency.

Difference a star makes

The Journal’s core argument is that Morningstar’s ratings systems are intended to be predictive, and as such they are not fit for purpose. “Most 5-star funds perform somewhat better than lower-rated ones,” we are told, “yet on average, five-star funds eventually turn into merely ordinary performers.”

The raw statistical data in the Journal’s article is not in dispute. Both parties accept the ratings are limited. But Ptak points out that the Journal’s analysis was just one interpretation of the data. “5-star funds,” he notes, “succeeded about seven-times more often than 1-star funds.”

Huebscher suggests, however, that the paper “could be vulnerable to the same criticisms [it levels at] Morningstar.”

To wit: the Journal’s own sibling, Barron’s, runs the Top Advisor ratings system — one that has been the butt of sustained criticism. According to an AdvisorHub report, an average of 60% of advisors who have made the top 100 list have at least one customer complaint, regulatory action or criminal conviction disclosed on their BrokerCheck records. See: Does Barron’s really have a bead on the best financial advisors in America?

Taking a different critical tack, the Journal also implies that Morningstar’s ratings are tantamount to an advertising pyramid scheme, referencing Hodges Capital Management Inc., a Dallas-based RIA that currently has $1.7 billion of AUM, according to its ADV.

“Hodges Small Cap Fund’s retail share class beat 95% of similar funds in 2010 but had less than $100 million in assets,” the Journal article states. “Late in 2011 Morningstar gave it a fifth star, and everything changed, said Craig

Hodges, who manages Hodges Capital Management. Charles Schwab put the fund on its ‘Schwab Select List.’ Mr. Hodges and his brother Clark decided to advertise the star rating on a billboard in Dallas/Fort Worth airport. Hodges Capital paid more than $10,000 to Morningstar for the right to advertise the stars, Craig Hodges said. By the end of 2014, assets in that fund reached about $1.6 billion, according to Morningstar data.”

Dow Jones uses a similar business model when its Barron’s unit rates RIAs and stockbrokers — charging them substantial fees to use the Barron’s ratings in their marketing. See: AdvisorHub slams Barron’s for its advisor list – correlating higher rankings with higher complaint rates

House disadvantage

The Journal also implies that financial services giants may benefit from Morningstar’s rating system. “Investment giants Vanguard Group and Fidelity Investments pay upward of $1 million a year for licensing, data and other tools from Morningstar. It’s unclear how much is just for advertising.” See: Fidelity, Goldman Sachs and Morningstar call 16 top reporters to New York to define the RIA alts problem — and to explain how their Dream Team solves it.

Although only 4% of Morningstar’s revenues can be attributed to the IP of which its ratings system forms a part, it is true that the firm gains huge visibility from its fund-rating services. Ultimately, the argument over the star ratings’ efficacy boils down to how you measure success.

For Morningstar, each ranking outperforming those below them is indicative of success. For the Journal, the stars’ eventual reversion to a three-star mean is evidence of a flawed system. Huebscher accepts the dispute is about semantics, but poses a different question: “What is the probability that a randomly selected 5-star fund will outperform a randomly selected four-star fund, where performance is measured based on raw returns or risk-adjusted returns?”

He continues: “The average probability of improvement over all five categories was 50.6%, barely better than flipping a coin.”

If the kind of analytical research that Huebscher uses in his critique of Morningstar was out there — and it was — why didn’t the Journal use it?

Phillips’ Oct. 26 response to the Journal, although ostensibly focused on the same statistical critique underpinning Kapoor’s and Ptak’s, draws a sharp line between the Journal and Morningstar.

“Casinos know we’ll overlook the small tilt the odds give them, not recognizing that their small benefits can lead to huge profits. We gladly forfeit that advantage and think we’re getting away with free drinks, when in reality we’re being played,” he writes. “Over time, little things mean a lot. The consequence of ignoring these tilts is their riches and our loss. The Journal’s article adopts the free-drink mindset, only in reverse. Rather than casually dismiss the casino’s advantages, it casually dismisses the advantages accrued by investors. It would seem foolish to dismiss that information.” See: Jack Bogle’s ICI grumbles and Kunal Kapoor’s ‘future’ mode make Morningstar’s 2017 conference sparkle with an uber relevance.

User error

A haunting sense that the Journal may have chosen the wrong target pervades its portrayal of a mutual-fund world rife with malpractice. Advisors “trumpet how much of their asset total is in 4- and 5-star funds as a sign of the companies’ ability to attract cash,” skipping due diligence, says the article. Funds are mis-sold and falsely advertised as five-star funds, and leading companies like Morgan Stanley fail to train their advisors on how to choose funds.

“You only have two funds rated by Morningstar — one’s a 2-star and one’s a 4-star,” says one former Morgan Stanley advisor in the article. “Go with the 4-star.”

Huebscher bridles at what he sees as Journal’s laying the blame for this squarely at Morningstar’s feet.

“As to the [Journal’s] use of anecdotal evidence, I agree that it could be interpreted that Morningstar is to blame when advisors make faulty fund selections based on the star ratings. But an overwhelming number of financial advisors are fully aware of the limitations of the star ratings. Advisors would clearly understand that it is they who are responsible for their fund selections, and I know of no evidence that supports the assertion that advisors place undue reliance on star ratings.”

Josh Brown, CEO of Ritholtz Wealth Management in New York, agreed in a blog post. “[Professionals] who cannot comprehend the idea that an outperforming fund is just as hard to select in advance as an outperforming stock, have no business even being in the industry,” he writes in an email. Ritholtz has $500 million of AUM.

“Morningstar didn’t make them uninformed, they already were.”

Shoot for the stars

“This is a fault with the users of the ratings, not the ratings,” Morningstar states in the Journal. “A high rating alone is not a sufficient basis for investment decisions.”

“We think advisors are looking for more from research firms.” Rosenbluth counters. “This is why CFRA built a more forward looking star approach combining holdings analysis, fees and relative track record. Advisors need more help with due diligence.”

“The stakes are exceptionally high,” says Huebscher. “If a vendor can reliably predict which funds will outperform, it would be able to charge significant fees from investors and develop licensing revenues from fund companies. So the search will go on.”

“Billions of investor dollars hang in the balance,” according to the Journal.

Yet, it is not for nothing that the “phrase past performance is no guarantee of future results” is so ubiquitous.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.